What do the belongings of Fritz Sievers say about him, or about the Second World War more broadly? Do they have any educational value, or are they toxic remnants of a genocidal regime? Are these things mutually exclusive?

Without contextual information, Sievers’ art, medals, and award certificates could easily be misused to glorify the Wehrmacht or whitewash its criminality. On the other hand, with the correct contextualization, a more nuanced picture might emerge. Over the course of the war, nearly 20 million men served in Germany’s armed forces and fought on fronts spanning Europe, North Africa, and several oceans. They were recruited from every region of Germany, every social class, and spanned several generations. This enormous scale makes it exceedingly difficult to distill a “representative” sense of the Wehrmacht as an organization. Rather, individual memoirs, letters, or material objects are representative of their authors or owners and the specific circumstances in which they were used. If anything of value can be learned from Sievers belongings, this context must be determined first.

The Eastern Front: December, 1943

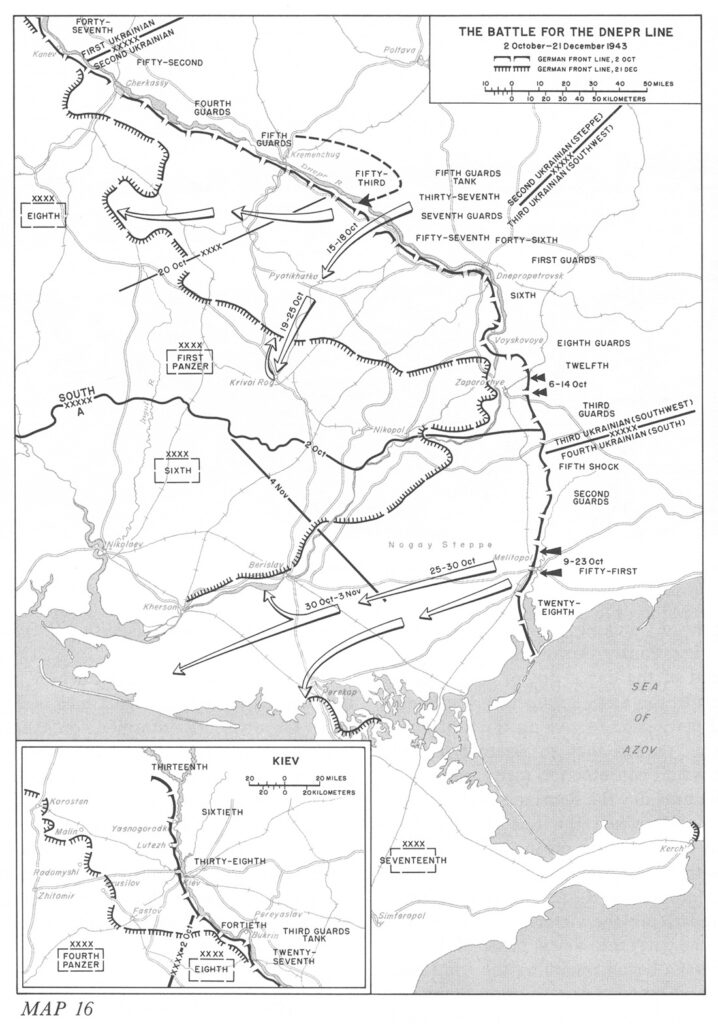

In order to understand the motivations behind Sievers’ artwork, it is important to determine the time and place that is was completed. Fortunately, a number of dates in the images and people and places depicted allow us to determine roughly where and when it was created. In it’s entirety, the art chronicles the experiences of the 111th Infantry Division, but the chronology ends in December 1943. At this point, the division was defending the Nikopol Bridgehead in southeast Ukraine. At right, a map details the German and Soviet positions in that area between October and December of 1943.

Propaganda or Memento?

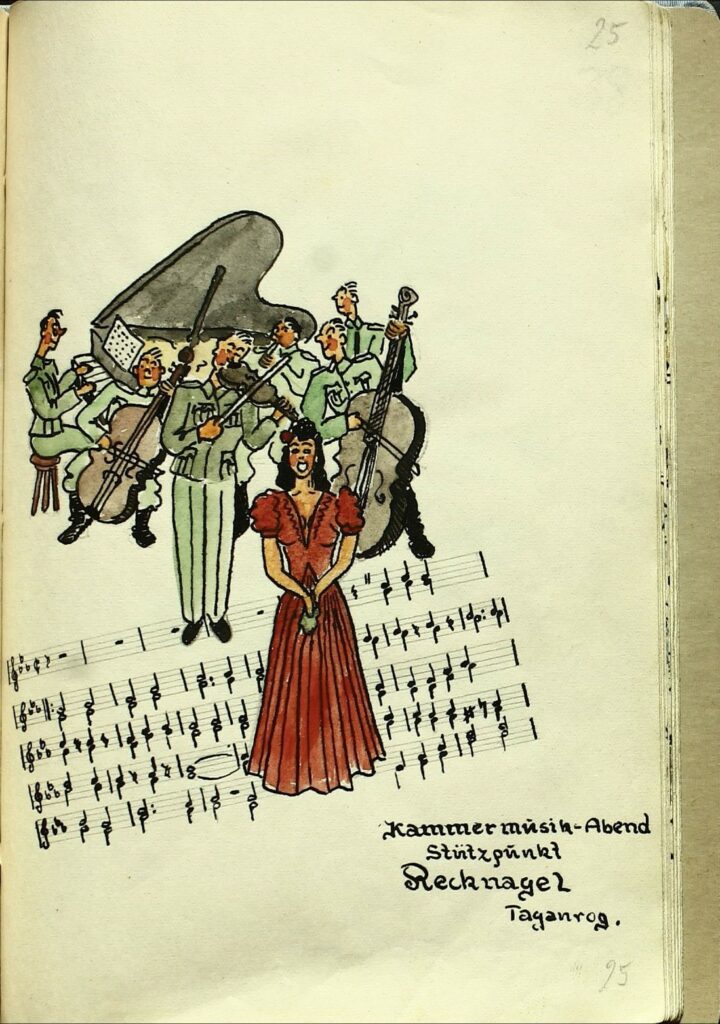

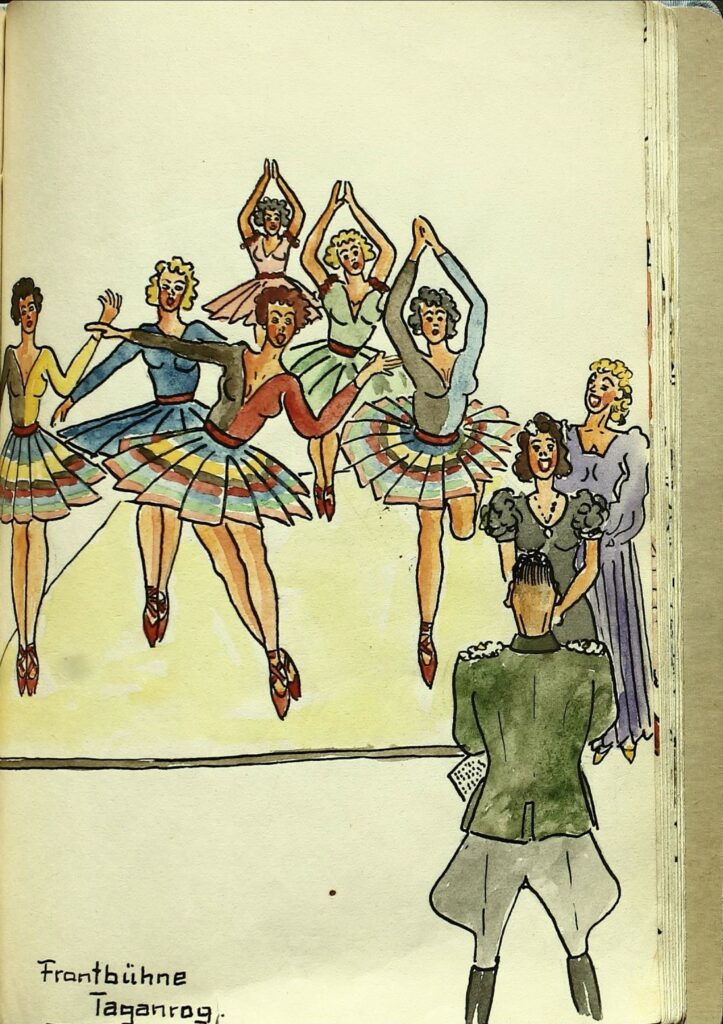

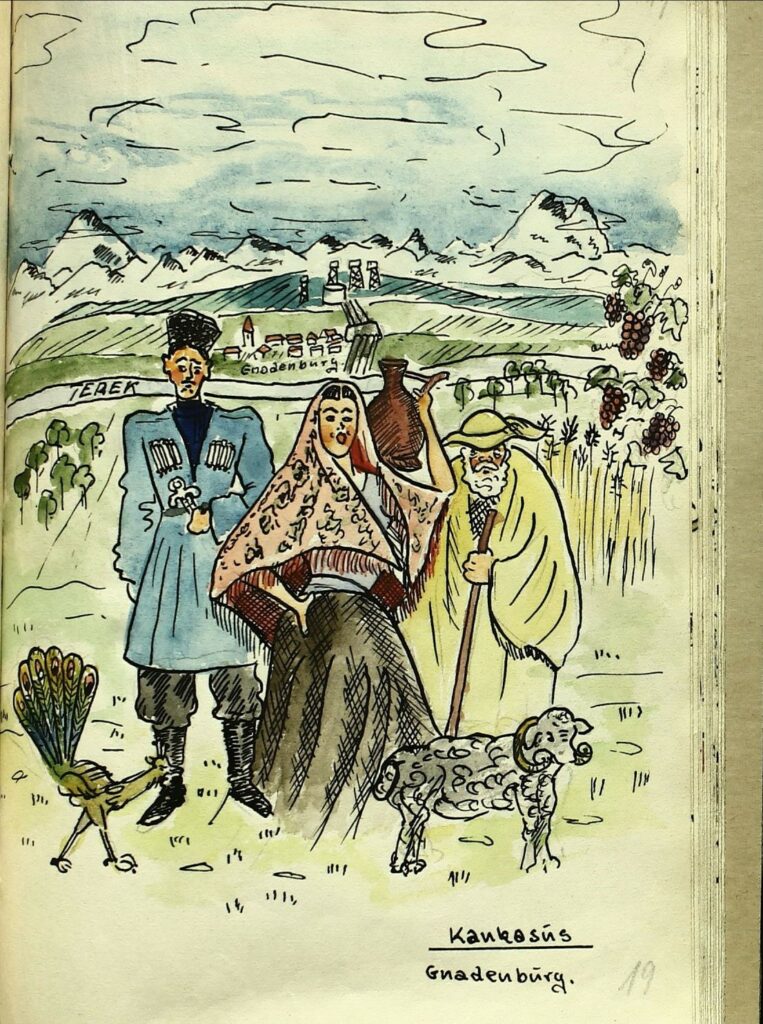

The art is probably the most intriguing item the group, but why was it made? Did Sievers create these illustrations for himself or others? He joined the division sometime in late 1941 or early 1942, yet the book depicts events and people in the unit dating back to 1940. Also curious is the distinct lack of combat in the illustrations. Instead, most of the images depict entertainment or caricatures of officers and civilians. Given the division’s military record, this omission seems odd. Since invading the Soviet Union in 1941, the 111th ID was almost continuously at the front. In 1943 alone, the division broke out of encirclement twice. Despite this, the tone of the artwork is distinctly lighthearted.

These factors heavily suggest Sievers was working in an official capacity. During the war, it was not unusual for Wehrmacht units to compose divisional war diaries for posterity as well as distribute unit newsletters. Naturally, these chronicles anticipated a victorious conclusion of the war, and, consequently, in words and art they evince an air of confidence and optimism. In all likelihood, Sievers’ paintings are part of an unpublished history of the 111th ID commissioned by the unit’s command staff during the war. Its perspective, therefore, should be understood as propaganda.

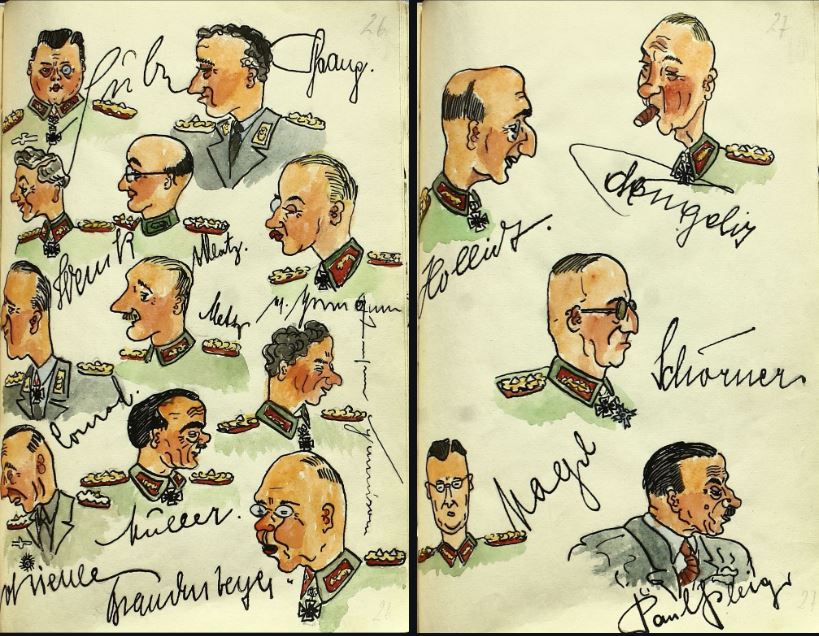

Army Group South Command, 1943

Given the context of time and place, many of the images begin to make more sense. Although untitled, the two pages below from Sievers’ artbook depict fifteen Wehrmacht generals and one Nazi functionary who held positions of responsibility in southeast Ukraine in 1943. Click on the image to learn more about each individual.

As Propaganda…

Again, taken as propaganda, the images in Sievers’ artbook can be properly contextualized as well as better analyzed. But it should also not be confused with state propaganda, rather this artwork was meant to boost the morale of a beleaguered division entering the third year of the war in the Soviet Union.

Given the timeframe of its completion, Sievers’ artwork collectively suggests the 111th ID’s men were war-weary and took solace in pleasant diversions from the reality around them. Rather than glorify combat or heroism in battle, the art emphasizes moments of tranquility and the paternalism of the division’s leadership. This omission is hardly attributable to poor performance or lack of experience. By the winter of 1943/44, the division had no shortage of military exploits. Twelve men from the 111th ID had been awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, one as recently as 18 October 1943.[1] Yet, Sievers makes no mention of these actions – in stark contrast to Nazi propaganda at the time lionizing its military heroes. Only two paintings directly focus on medals, and they represent collective achievements rather than individual heroism. The first is an image of the Ostmedaille (Eastern Medal) awarded to troops present during the winter crisis of 1941/42, while the second shows a man listening to a radio announcing the award of the Oakleaves of the Knight’s Cross to the 111th ID’s commanding general, Hermann Recknagel, for leading his troops out of the Taganrog encirclement. Both events, the defense of German lines during the winter crisis and successfully breaking out of Soviet encirclement, recognize collective achievements of the division rather than individual soldiers. This reinforces German historian Thomas Kühne’s conception of the Wehrmacht as an army motivated primarily by unswerving loyalty to the group, be it a squad, platoon, regiment, or division.[2]

Overall, the art’s overriding emphasis on peaceful moments strengthens the hypothesis that Sievers made it for wider distribution and, given the 1943/44 timeframe, provides a glimpse of how propaganda functioned within Wehrmacht units at this later stage in the war. However, whether this is conscious propaganda is difficult to tell. In an analysis of German POW conversations, historians Sönke Neitzel and Harald Welzar found “commonplace routine was only one of the things the soldiers didn’t talk about. Another was emotions, or sheer concern for one’s own survival. These topics rarely crop up and previous research has shown that soldiers generally filter them out of conversations.”[3] Neitzel and Welzar also concluded that “war is work” despite its deviations from normal life.[4] As such, the workers of war, i.e. soldiers, tend not to view death, brutality, and violence as abnormal or conversation-worthy. This is not to say soldiers are not stressed or traumatized by these events, but that they are experienced regularly and collectively, leaving little reason for soldiers to discuss them with one another. So, while Sievers’ art does reflect a certain level of propaganda, in that it was likely intended to boost morale, it also reflects a natural inclination among combat troops to avoid the unpleasant realities of warfare. It is important, however, to underline the “unhappy” events that Sievers omitted.

[1] Friedrich Musculus, Geschichte Der 111. Infanterie Division, 1940-1944 (Hamburg: Traditionsverband der 111. Infanteriedivision, 1980), 428.

[2] Thomas Kühne, The Rise and Fall of Comradeship: Hitler’s Soldiers, Male Bonding and Mass Violence in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2017). 76.

[3] Sönke Neitzel, Harald Welzer, and Jefferson S. Chase, Soldaten: On Fighting, Killing, and Dying (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012). 55.

[4] Sönke Neitzel, Harald Welzer, Soldaten, 334.